10. Yi yi(2000) Directed by Edward Yang

In his nearly three hour masterpiece, director Edward Yang follows the daily lives of a Taiwanese family in crisis. Following a wedding, the story is set when the grandmother suffers from a stroke and lies unconscious in a coma. Doctor’s orders are for the family to talk to her. In attempt to awaken the grandmother, the family at the same time discovers their own hollow lives as they repeat to her the same prayer-like monologue every day.

Father of the family, NJ, crosses paths with an old first love, and from there on is tormented with thoughts of his life had he not left her years ago. NJ’s wife is distraught by a blank life, and in resolve, goes on leave for a Buddhist retreat. Meanwhile his daughter is caught up in a love triangle with a young man who mirrors her father’s cowardice.

But it’s NJ’s son who best delivers the message that Yang sends throughout the film: live wholeheartedly without looking back. However, therein also lies the dilemma. And so Yang-Yang takes it upon himself to photograph the backs of people’s heads, to reveal they cannot see what’s behind them—an inescapable flaw passed down every generation.

In a discussion with Japanese game mogul, Ota, NJ is told that “people want a magician,” but Ota reminds NJ that there is no magician.

9. Mulholland Dr.(2001) Directed by David Lynch

Endless discussion has been devoted to this multi-genre nightmare on Hollywood and the subconscious of stardom. With each viewing, a bit more of the meaning and symbolism comes to light, leaving the audience with a better or different understanding of Lynch’s intentions.

But to get caught up in the specifics of the symbolism and commentary can be to ignore the mastery of Lynch’s ability to manipulate the atmosphere and mood of his films. Upon first viewing, the first half dozen scenes seem hardly connected in meaning, but unified through tone, slowly unveiling the mystery and tragedy of the jilted, aspiring actress’s psyche.

The second half of the film reestablishes the purpose of the first, feeding details to the audience while remaining captivating and breaking down established plot conventions. In the end we’re left asking for more, almost ready to start over from the beginning and remain in Lynch’s twisted, horrific loop.

8. Regular Lovers (2005) Directed by Philippe Garrel

One of my top cinematic wishes is for the films of Philippe Garrel to become more widely available, particularly those involving Nico. I was lucky enough to see The Birth of Love at the Seoul Cinematheque, but otherwise Regular Lovers is the only Garrel film I’ve had the pleasure of viewing and remains to be the most readily available.

Exquisitely shot in black and white, the film recalls the May 1968 protests in Paris. Rather than focusing exclusively on sexual liberation, the film investigates the time more chronologically, starting with the riots, but more interested in their aftermath.

Garrel is sympathetic towards the youth and their actions, despite their inevitable flaws and at times misguided beliefs. Like Godard’s Masculin feminin, the characters never actually carry out their ideals but use them as a means for creating another niche for themselves in a capitalistic society. Sitting around all day smoking opium may very well be anti-social, but it hardly changes anything for the better.

As such, the film celebrates the revolutionary spirit of the youth, but regrets the ease with which their purpose is derailed. This is a very nostalgic, naturalistic film that belongs in the same breath as the French new wave and other brilliant French films of the 60’s.

7. Distance(2001) Directed by Hirokazu Koreeda

In 1995 the Japanese religious cult Aum released Sarin gas in the Tokyo Subway killing 12 and affecting over a thousand others. Distance follows the aftermath of a similar, fictional cult’s actions which results in the death of 128 people. However, the focus of the film is not on the ideology or historic importance of the disaster, but rather the way it affects the relatives of the perpetrators.

Every year four relatives of the deceased members (two spouses and two siblings) gather at the cult’s former camp site to pray for their loved ones. The group hardly knows one another and spends the day hiking and making small talk, never mentioning their relatives or their misguided actions. When they return to see that their car is missing, they have no choice other than to follow a solo remaining cult member to the cult’s cabin in the woods and stay the night. Here they are finally forced to confront their guilt, sorrow and lack of understanding over their relatives actions.

In a series of chilling and mesmerizing flashbacks each individual ponders the moments leading up to their loved ones eventual departure. In the final third the film picks up pace, throwing in a twist that serves to give the film all the more ambiguity and accentuate the themes of grief and guilt.

As with all of the director’s best work the film forces the viewer to contemplate the motifs in connection with his or her everyday life. How close are we really to our loved ones and why do we feel shame or responsibility for their ideologies or actions? Is the distance between us surmountable? Questions like these permeate Distance, and few are left answered by the film’s well shot and conceived conclusion.

6. Tropical Malady(2004) Directed by Apichatpong Weerasethakul

What begins as a conventional romance suddenly evolves into a mythic parable of love and conquest in this highly original, genre bending work from Thai auteur Apichatpong Weerasethakul. The film is split into two nearly equal parts: the first tracking soldier Keng’s courtship of illiterate farm boy Tong, and the second following Keng in his hunt for a beast that is killing the village’s livestock.

In the opening hour we watch as the two go through the typical acts of flirtation and lust. The contrast between Buddhist rural Thailand and city life is ever present as the two switch back and forth between Tong’s home and the nearby town. In one scene we watch as six doctors absurdly hover over an X-ray of Tong’s pet dog, while in another the two lovers accompany a villager through a dark and cramped temple cave.

It is in the second half where Weerasethakul”s propensity for the audacious and transcendental occurs. As Keng chases the monster into the jungle, a monkey talks to him, warning that the beast will devour his soul. Shots of Keng listening to the surrounding fauna at night are intercut with cave-like paintings and voiceovers recalling the folk tale of a shaman who’s soul is trapped in a tiger. This gives the film a very naturalistic feel as we begin to wonder who is the predator and who is the prey. Beyond that Weerasethakul is focusing on the spiritual nature of love and its power to consume. Few pieces of art have the power to do just that to its viewers with such freshness and creativity as Tropical Malady.

5. Code Unknown(2000) Directed by Michael Haneke

Parisians of diverse backgrounds collide in this exploration of social life in the globalized world. The characters’ lives are revealed through a series of personal, naturalistic vignettes, jumping in and out at seemingly random points in the action. The elliptical editing reflects the way we experience strangers in real life, perceiving others based on their race, actions, economic standing, etc., and quick to judge others without knowing their true characters.

Haneke does well to contrast the tension in these scenes where the characters abrasively and defensively interact with one another as strangers, with those in which they are with family or friends, being themselves at home. There is a strain of fear and uneasiness pervading the public scenes of the film, first introduced through the initial provocative scene, and culminated perfectly in the penultimate scene on the subway— one of the most horrifying, yet truthful moments in cinematic history. Haneke’s films force confrontation with our own social discomfort and anxieties in ways that few others do. And perhaps none of his work does this better than Code Unknown.

4. Khadak(2006) Directed by Peter Brosens and Jessica Hope Woodsworth

An epileptic nomad and his family are forced off their land, into working in a mining town by the government, ostensibly due to a plague affecting their sheep. The young man, Bagi, has increasingly frequent seizures, accompanied by destructive visions and prophetic encounters with an old shaman of his tribe.

This is the basis for Beligian co-directors Brosens and Woodworth’s surreal, poetic masterpiece on industrialization and cultural annihilation. The breathtaking images shift between vast, snow-covered planes and crude mining sites, combined to give a desperate and apocalyptic feeling to the film.

The struggle of Mongolia and the nomadic people is championed through a maze of captivating hallucinations, viewed through the mind of Bagi, as he attempts to save his people with his transcendental powers. Metaphorically rich, Khadak is one of the most original films of its time, leaving plenty to ponder upon repeated viewings.

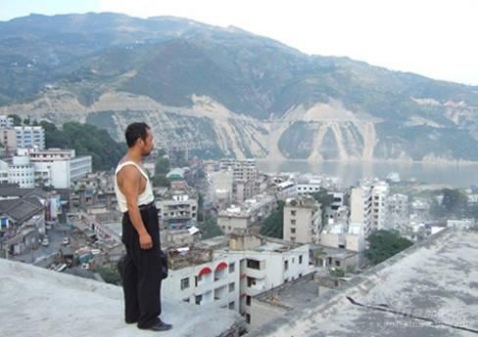

3. Still Life(2006) Directed by Jia Zhang Ke

Displaced characters and a part of China are sinking under water in Jia Zhang-ke’s Still Life. In the beginning we see a stoic Han Sanming looking over a valley full of water, on the bottom of which his 2,000 year-old home town lies, and above floats a large boat. Han and other characters are victims of some distant entity decomposing the places around them.

The Three Gorges Dam project proves to be the face of this entity. For work, men are swinging hammers into the very walls that were their homes. Their relationships with one another are uncertain as they try to connect with the change of times.

More than sending a message, this film is concerned with painting a world of a China where people survive in the rubble of ancient cities and days are broken up by the toppling of buildings. Scenes are composed of both a bleak reality as well as the vibrant color of life. The complete painting results in a sad and absurd human condition that is alone and wiggling through every moving image. A woman cools herself by standing in front of an oscillating fan. She hangs a single colored shirt on a line to dry, just as a building falsely launches into the sky. A scene of men in white suits spray chemicals over a demolished town is followed by a boy singing about working hard and being true to love.

Jia said that when he sees history, it’s a combination of what really happened as well as his imagination at work. This world is neither true nor false, but rather an observation of simplicity and loss.

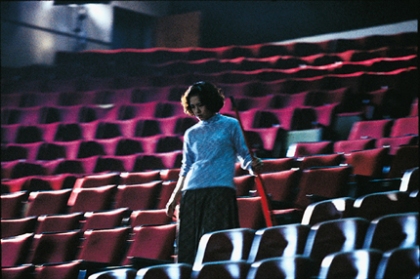

2. Goodbye Dragon Inn(2003) Directed by Tsai Ming-liang

A run-down movie theater plays an old martial arts classic with hardly anyone there to see it. Those that occupy the theater are more concerned with finding human connection. The lame ticket lady hobbles around, taking a steamed bun up to the male projectionist only to be disappointed to find him absent.

This is about as far as the plot goes in a film without a single line of dialogue until the 45th minute. It is pretty clear that the abandoned, leaking theater represents Tsai’s viewpoint that the cinema going experience is disappearing, unable to compete with home theaters and online streaming. So what else is being said in a film with such sparse action?

In an oddly provocative scene Tsai focuses his lens on the lit theater after the film has finished playing and the seats are completely empty for what seems like a couple of minutes. This appears if anything like art for the sake of art, but really it is a challenge from the director for the viewer to not walk out on the film. After all, why go to a film of this ilk and expect explosions, sex, and rapidly developing plots and then leave halfway through without giving the piece any thought? It is this lack of work on the audience’s part that Tsai is lamenting.

Beyond the death of film there is a humorous scene commenting on the awkwardness of those crowded urinals after the film lets out, and a ghost haunting one patron with its stinky feet. There are lots of other layers to peel back, showing us that film can be much more than just a slightly entertaining piece, watched on a notebook to pass the time.

1. What Time is it There(2001) Directed by Tsai Ming-liang

Occupying the top two spots(and another in the top 15) is the holder of the best director currently working title, Malaysian born-Taiwanese auteur Tsai Ming-liang. On display in his finest film, are his trademark touches, motifs and magic.

Critics often complain about the pacing and nihilism of Tsai’s films, but because of the dedication and unending detail packed in every shot, I never find myself bored or anxious. He uses space as well Akerman in the 70’s, giving the viewer a peek into the private lives of his desperate characters. Like Jeanne Dielman we enter these characters’ worlds, suffocated by their environment and fighting with them to escape.

Tsai is also a master of lighting, using an array of colors to compliment the mood of his fancied shots of dimly lit interiors and alleyways. This film takes us inside a grieving family’s home, lit only by candles and a fish tank. This is because the wife claims that her husband’s ghost likes as little light as possible. Her desperation and loneliness shifts from tragic to comical as we watch her perform rituals and cook for her deceased husband in hopes that his spirit may return. The balance of humor and forlornness gives the film an absurd appeal, confirming our nihilistic tendencies while planting a small seed of hope, in the utter fascination with human life.

Ghostlike themselves, the three characters drift through their surroundings, hardly interacting with those around them. The wife tries to fight her loneliness with spiritual nonsense. The son changes all of the clocks to Paris time and watches French movies in order to feel closer to the woman he briefly met and fell in love with, who is now in France. Their daily struggles are interwoven masterfully, coming to a climax near the end when all three ultimately try to quell their despair through sexual means. By the end of this scene all three hit rock bottom and the pessimistic worldview is firmly established, only to be completely turned on its head by the breathtaking, ambiguous ending that could only come from a masterful director operating at the peak of his powers.